Quince Jam

"If only rocks could talk, they could tell everyone what we've been through,” my mother says holding a knife in her hand. She’s using it to cut quince. She takes the yellow skin off with the precision of a surgeon, and then slices the dense mass into thick, skinless slivers. We sit in silence as each piece falls into the bowl, our minds on a war unfolding thousands of miles away in a small, unrecognized republic called Nagorno-Karabakh (or Artsakh), that doesn’t mean anything at all to most people in the world.

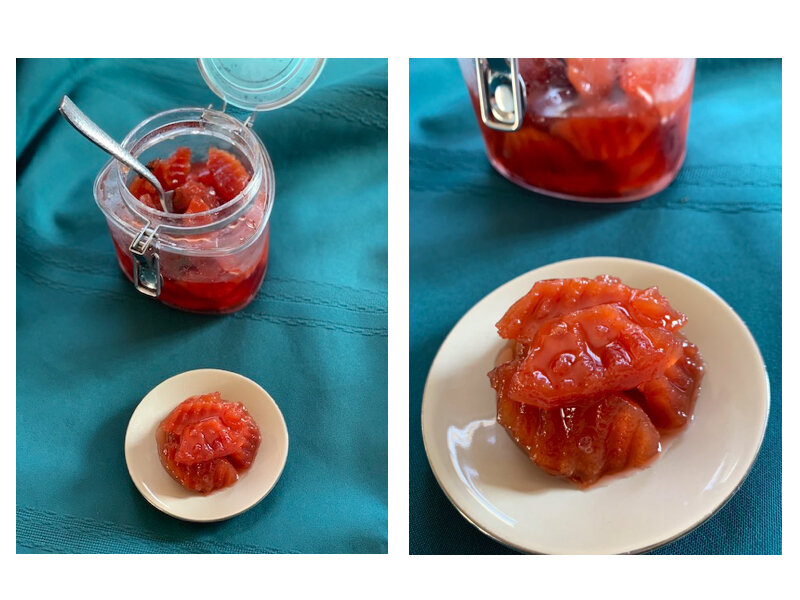

In a couple weeks, as the blood-red cooked quince sits in glass jars on the kitchen table, the war will end, and a new cycle of loss will emerge.

Thousands killed, an entire generation gone. Even more wounded, their futures now forever tied to what took place on the battlefield.

War, or its aftermath, is not an original or unique story.

But for Armenians, loss - of people, of places, and of potential for a dignified life - has never been just a one-off event. Instead, it is a cycle that keeps repeating, manifesting itself over and over again for hundreds of years in different ways. There are deep, painful reasons we number just 10 million in the world. There are deep, painful reasons we are spread across it, in every crevice and corner from Southern California to Singapore. Those weren’t choices we made, they’re the result of having no choice to begin with.

History like that doesn’t leave you. You move on, live life, and accomplish greatness despite the circumstances that could have ended you.

But it lingers around for generations, just beneath your skin, like a faded bruise that still feels sore when you push your thumb down on it from time to time.

This is why, in our Los Angeles kitchen thousands of miles away and a couple generations on from events that led my great grandmother to hide in a church fearing for her life, my mother speaks of rocks - rocks that bore witness to each and every cycle, rocks that protected those who survived, rocks that continue to stand in the places we no longer do.

The quince is like a rock, too. It’s a tough fruit, neither popular or palatable in the West. The process to turn these pale, hard lumps into soft, amber colored slices drenched in syrup requires time and experience. Their season comes around at the end of the year, a time that will now forever be marked in the Armenian psyche as one that bore the newest cycle of death and destruction.

An ancient fruit, the quince’s native land is in Western Asia, which includes Armenia, as well as several neighboring countries. Some theories point to the quince as having been the actual forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden, instead of an apple.

In Armenian, quince is “cer-keh-vil” or սերկևիլ and a prominent part of our food culture. Its toughness and high pectin content make it a perfect candidate for preserving. It also has anti-inflammatory properties. Its seeds are known as a folk remedy for coughs and sore throats in the region: they’re soaked overnight in water, until they turn the water into a gooey, thick gel which is then drunk. Some Armenian families like mine stuff them with rice and meat before cooking.

The quince features in a lamb stew called “shoushin bozbash” which is “practically unheard of outside of the Caucasus” writes Sonia Uvezian in her 1974 cookbook, “The Cuisine of Armenia.”

The quince is also associated with exile, a reoccurring theme baked permanently into the Armenian story.

It appears in a poem translated by journalist and suffragist Alice Stone Blackwell that one Kansas newspaper titled “Homesickness” in 1905.

First published in 1896 in a volume called “Armenian Poems: Rendered Into English Verse,” during the era of the Hamidian Massacres, where more than 100,000 Armenians were killed and more displaced, the poem’s narrator longs for a homeland that can no longer be accessed:

“I was a quince-bush growing on a rock, a rocky cliff rose above the dell.

They have uprooted and transplanted me unto a stranger’s orchard, there to dwell. And in this orchard they have watered me with sugar-water, that full sweetly flows.

O brothers, bear me back to my own soil, and water me with the water of the snows!”

Blackwell worked to bring poems like this one into the English language with the help of Bedros Keljik, a pioneer of the Armenian community in Minnesota who survived a forced march in the desert as a teenager before finding refuge in America. Born in Kharpert (present day Harpoot, Turkey), Keljik became a rug dealer, collaborated with Blackwell translating poems and wrote vividly about the complexity of the Armenian-American experience.

Over a hundreds years on from the era of mass violence inflicted on the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian population, the Hrant Dink Foundation began publishing oral histories of Armenians whose roots traced back to cities across Turkey before the Armenian Genocide as a way of preserving memories at risk of disappearing.

In a book about the Armenians of Izmit, one contributor recalls typical Armenian dishes from Izmit including quince and plum stews, but even when speaking of food, the central Armenian theme of exile reemerges:

“Of course,” the interviewee says, “we’ve lost all of that.”

2020 brought Armenians a new era of loss. Suddenly, we began to live our history in real time. There was no need for black and white photos, no old newspaper clippings, and no need to explain the pain. We saw it, unfolding in front of us, hearts broken and helpless while the world looked away, and felt the deep, pulsing ache of that bruise once more on our skin.

These fresh wounds - the ones endured by young soldiers who sacrificed their lives as well as their sanity - and the anguish felt across the global Armenian world, are here to stay. They’ll be discussed for the next 30 years between bouts of thick black coffee and mulberry vodka - what went wrong? who is responsible? what could have been done differently? Table top fodder for another generation to digest, as the future remains uncertain and the existential fear is hard to shake.

We have to sit with this pain for now. Endure it. Live with it. Wrestle with it. Put it to work. The only way out is through.

My mother and I sit with the discomfort of the quince, too. We endure it, wrestle with it, and put the fruit to work. Somehow, we attempt to create something beautiful out of rocks.

Quince Jam

2lbs (3 medium sized quince)

4 cups sugar

1 cinnamon stick

Several whole cloves (to taste)

Wash, cut, core and peel quinces. They’re often cut like apple slices, but a crinkle cutter can also be used to give them a different look.

Put the sliced and peeled quinces in a large pot, filling it with just enough water to cover them. Cook on a medium to low heat with the lid on until they change color, from pale white to gold.

Add sugar, cinnamon stick and cardamom pods (sometimes vanilla is added too depending on your taste)

Cook on low heat, simmering until the quinces become tender and turn a brilliant red color (Usually 2-3 hours)

Remove from heat, ladle into sterilized jars and seal.